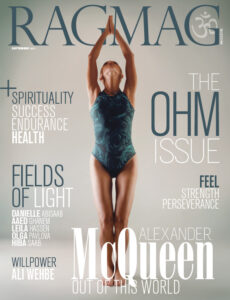

Cover page, images courtesy of RAGMAG magazine

When British fashion designer and couturier Lee Alexander McQueen hung himself in February 2010, days before London Fashion Week, family and friends dressed in his designs to the funeral. For most iconoclastic designers, fame flourished after decades of hard apprentice and new contributions to the fashion world, but for McQueen it came sooner with his raw introduction of the romantic sublime when he created his own fashion label.

Romanticism for McQueen, aroused an exploration of nature’s philosophical concept of the sublime. A representation of his emotional state such as awe and wonder, fear and terror. For fifteen years, in supreme degree, his runway shows elicited feelings to what he associated with the sublime: tempestuous seas and twisting winds, starry skies and rugged mountains, melting ice caps and rolling waterfalls. His show concepts—rare, avant-garde, beautiful—preceded his designs. Beyond that, he explored historical romantic movements: gothic, nationalism, exorcism, primitivism and naturalism to further animate inspiration. As a romantic, imprisoned in two previous eras, McQueen constantly demanded reactions for his visions.

It was in 1992, when international style icon Isabella Blow bought McQueen’s first collection; his master degree graduation collection. Immediately, his “mutated jackets”—business suit jackets with organic patterns, raised shoulder padding, rounded dropped necklines—provoked her tastes. Supportive of his tailored mastery, she helped launch his career first as an apprenticed tailor. His clientele included Prince of Whales and Soviet statesman Mikhail Gorbachev.

As a skilled master of optical illusion, McQueen launched the “bumpster” collection shortly thereafter. He cut trousers alarmingly low at the back to reveal the buttocks, an area he found most attractive. Surprisingly, a tour guide at “Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty” exhibition at New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, believed he got the idea from plumbers bending under sinks to fix pipe leakage.

McQueen referenced Gothic novels, serial killer Jack the Ripper, and everyday prostitutes in his early career. “One of his mother’s ancestors owned an inn, wherein Ripper’s victim once lived,” another tour guide told me. Some suits had amulets of hair attached to its waste bands. He got the idea from prostitutes who cut their hair, placed their locks in glass amulets, and gave them to their lovers.

Eventually, he fully explored the Victorian gothic era by drawing references to the deeply melancholic writings of Edgar Allen Poe, black crow and raven film imagery of Alfred Hitchcock, and dark, quirky-themed animations of Tim Burton. In Dante (fall/winter 1996-7) and (autumn/winter 2002-3), McQueen incorporated resin casts of vultures, dried black duck feathers and black silk to give his designs a sadistic and Frankensteinian feel. As a result his creations looked like theatrical costumes; Phantom of the Opera, Zorro, and Three the Muskateers.

In this period, McQueen was accused of masochism for his use of fetish, to which he responded: “I think there has to be an underlying sexuality. There has to be pervasiveness in cloths…there is a hidden agenda in fragility of romance. It’s like the ‘Story of O’[a French authored book on sodomy]. I’m not big on women looking naïve. There has to be a sinister aspect…” Again, his message was as such: melancholy and mourning, not aggression against women.

Courtesy of Alexander McQueen

In fact, women became his closest allies. His collaborators were mostly women and his friends included supermodel Naomi Campbell and Sex and the City actress Sarah Jessica Parker. McQueen had many heroines, historical figures: Empress of Russian, Catherine the Great; national heroine of France, Joan of Arc; Queen of France, Marie Antoinette; and Virgin Queen of England and Ireland, Elizabeth I. All were strong, noble, and rebellious like McQueen.

McQueen of French and Scottish descent, was raised a proper Englishman in East London. Openly gay, he was always sensitive to heritage and culture, race and class. He clung to his French mother, Joyce, who died nine days prior to his suicide. His father, a Scottish taxi driver, provided his son with the foundation of national Scottish pride. Throughout his career, McQueen was unsuccessful at separating fashion from politics, inviting much disapproval in fashion circles.

Consequently, his penchant for romantic nationalism was woven and patterns of negative attitudes towards England and sympathy for Scotland, took shape in his most recent work. Widows of Culloden (autumn/winter 2006-7). He reminded his audience of their nation’s “rape” of Scotland in the 1745 massacre of the Scottish Jacobites. In Highland Rape (autumn/winter 1995), which greatly pushed his career, he featured battered models in torn Scottish print to make his nationalism clear. “Shorn of its original rawness and anger, the result was a poetic and technically accomplished tale that involved romantic images of Scottish fantasy heroines…,” reported online magazine Style.com. Ironically, he once showed up with Sarah Jessica Parker in Scottish prints for the museum’s AngloMania event.

In contrast, The Girl Who Lived in the Tree (autumn/winter 2008-9) captivated a hail-Britannia motif rendered in tulle, embroidery and fur. Based upon a fairy-tale inspired by McQueen’s 600-year-old elm tree in his East Essex garden, McQueen used the metaphor of a girl coming out of the dark tree to meet a prince and become a queen, to portray the mourning of Queen Elizabeth II. Heavily injected with irony, he featured Victorian Goth ballerinas in muted punk plaids.

Delving into romantic exorcism McQueen focused on the politics of appearance, questioning the fashion world’s portrayal of beauty. In Spring 2001, McQueen made a bold move: he seated his audience around a mirrored box. They weren’t able to see inside, only to watch their own reflections. Voss intended to produce an intense and paranoid self-consciousness. Once the cube was lit, models in bandages, strait jackets and kimonos, head-banged their heads as if they were trying to escape a mental-hospital holding cell.

Courtesy of Alexander McQueen

This climatic performance was replicated at the exhibition where a video filmed a shattering cube, uncovering a plump model reclined on a couch. The model, fetish writer Michelle Olley, had her face covered and wore a breathing tube. According to a guide, it had another meaning: pitting East (Japan) against West (America), inspired by the struggle of good versus evil in Harry Potter’s “Sorcerer’s Stone.”

Sarah Burton, the current Creative Director of Alexander McQueen, spoke with Vogue about the late designer’s red dress featured in Voss, before the exhibition’s opening. “So much of this show was about the collective madness of the world…Lee wanted the top of this dress to be made from surgical slides used for hospital specimens, which we found in a medical-supply shop on Wigmore Street. Then we hand-painted them red, drilled holes in each one, and sewed them on so they looked like paillettes. We hand-painted white ostrich feathers and dip-dyed each one to layer in the skirt,” she said. What Burton described was the designer’s spontaneous creative process. He never finished one of the sleeves.

McQueen further championed authority of imagination and freedom of thought. His most eccentric pieces are featured in his “cabinets of curiosities” displayed at the Met. They include Philip Tracey’s and Guitto Palau’s headpieces; fabric butterflies, wooden birds and cork Chinese gardens. Inflamed by art and fashion history, McQueen created metal spine corsets, resin horns and body suits made of leather and horse hair.

Also on display, are video selections of his runway shows: emotionally passive-aggressive, methodically unorthodox, stylistically radical. He painted sad joker faces on models and fastened skeletons to their knees, brought carousels and industrial machines on stage, built fires and checkerboard sets (referencing the Sorcerer’s Stone again) using his imagination to set himself free.

Importantly, McQueen often glorified the state of nature during his primitive phase. African tribes, dress rituals and Yoruba mythology served as themes for It’s a Jungle Out There (autumn/winter 1997-8) His wildlife fashion was dubbed “silhouettes of the decade.” McQueen transformed the silhouette, saying, “To change the silhouette is to change the thinking of how we look.” Irene (spring/summer 2003) told stories of shipwrecks, pirates and conquistadors. He explored the history of tribalism in Nihilism (spring/summer 1994), witnessing “noble savages living in harmony with natural world.

Courtesy of Alexander McQueen

Romanticizing the terrifying, big and overwhelming power of nature, brought McQueen closer to naturalism. Rather than exploring Charles Darwin’s “Evolution of Species,” he focused on humankind’s devolution for Plato’s Atlantis (spring/summer 2010). As extraterrestrials, models wore heels styled into beehives. Dreams and personal fears invigorated his visions, often impractical when translated into design. As an experienced diver, he witnessed the negative impacts of climate change on our planet and its oceans. The show, streamed live on the web, also intended to demonstrate “time compressions produced by the internet,” said McQueen, and create a conversation between creator and consumer.

How deep McQueen examined nature and analyzed dark facets of the romantic movement, can arguably be summarized in Angels and Demons—the show he never finished. A month after his death, the small show privately premiered for a small group of designers in Paris. His designs, shaped by the asceticism of Flemish art in 15th century Netherlands, were concealed in a gilded casket. He used imagery; annunciations of angels and the Virgin Mary, painted on alter pieces to prompt his collection—including the infamous gilded duck-feathered jacket He also exercised fashion manufacturing: transcribing photography on fabric, to enliven a new style.

Today, the darkly glorious designs of McQueen, leaves many with the uneasy pleasure of his artistic expression. McQueen, his own biggest critic, impresses with a sense of grandeur and power, the way painter Tudor did in his paintings of the rolling swell of high-seas. Though drowning in his own storm, the romantic continues to take us on journeys we’ve never dreamed of, forever stretching our imagination.

The full featured article in RagMag September 2011 (PDF)

[issuu width=550 height=359 pageNumber=105 backgroundColor=%23222222 documentId=111007102955-4082484193bd40fc9a073640b90e5b50 name=ragmag_september_2011 username=ragmag tag=aaed%20ghanem unit=px id=046b28f3-b4c8-beeb-2ac6-4269df306f6a v=2]