Oban, copyright Kosta Grammatis

Sequencing flat hills outside of Edinburgh, slipping in and out of cloud shadows, paint a pleasant postcard of the Scottish countryside. As fog and rain rob the blazing sun, only darkening shades of green, I wonder if all that I have left are steeples roads serving as my true markers.

The roads insist on turning me to the left and then to the right, and rolling me up and down like a wooden wine barrel lost on a violent river. Its sudden curves, narrowing and widening of passage, and the constant arcs of shadow of the wide hills during the course of a day’s bewildered excursion—all make for a gloomy and lonely car ride.

If it wasn’t for the Johnny Walker golf courses, decaying cemeteries and meadows populated by sheep, Scottish fields would have been a disappointment.

The grass along the road, trimmed neatly, is further lowered to the ground by pasture-fed sheep huddled together in blankets of white. Scotland is fond of these cultivated creatures; their wool keeps the Scots warm throughout the seasons.

But I am in search of another resource: fish, fried, and served with chips. In Scotland’s seafood capital of Oban, dressed with stone castle estates with weeded ponds, fried fish is plentiful. Called “fish and chips,” the Scottish delicatessen comforts many during torrential downpours.

An old RV behind an older bunker in Oban, copyright Kosta Grammatis

Under pouring rain, children in woven sweaters run after birds flying low to the ground as if weighted down by dark clouds. They raise their canes, their eyes adjusting to the early evening haze, suffusing patches of green dotting the gentle hills. The sheep hold their ground, and I worry since they never take shelter.

Closer to the city, I check my road map—now upside down—which serves me little purpose as roads bear no signage. Lighting posts have been turned off leaving me with only my headlights, my sole source of light. Luckily, the beams pick out silhouettes walking along the approaching port. I spot some fisherman and asked them for cheap accommodations since I spent all my monies on gas.

They point me in the direction of a white cottage perched on a hilltop at the end of the seaside road. Rented by an old Scotsman named Leonardo, the cottage used to be an old bunker salvaged after World War II.

Leonardo offers his home to mostly couch surfers whom follow his instructions of bringing beer upon their arrival. He never accepts cash for his kindness, offering a burning stove, hot tea, and bunk beds for travelers arriving from all places like London and Toyko. He sleeps next to the stove, on a bed that unfolds from the wall, in the kitchen.

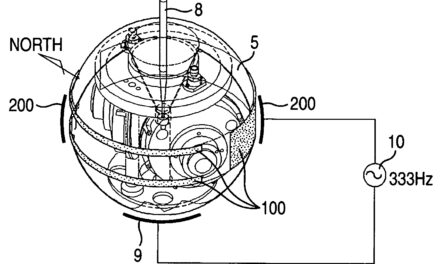

Once the bunks fill, he points to rusty a RV camper sitting in the backyard. Resembling a computer laboratory, monitors litter the floor underneath dangling wire. Circuit boards and chips are tugged away on medal shelves while lithium batters and beer caps sprinkle the floor. The mattress is dusty, and blankets full of lint. No sheets.

I study the electrical appliances like school text books and think of the eight hour drive which began in Edinburg, of the fish’s compact bone skeleton, of the vendors feeding men of sea, of the seals rubbing their tales against the stern of their boat, not knowing what brought me here.